Merry Christmas cards 12 times a day? The Victorian way

Stressing out over mailing deadlines for Christmas cards and presents ?

In 1880, the Victorian postal service made its first ever plea to post early for Christmas.

No later than the 24th of December, please!

Christmas Day mail service was restricted to only one delivery.

A very British problem, indeed.

Would you pay to receive your mail?

Prior to 1840, the recipient paid the postage!

For a working-class person, a letter of middling length could come to about a day’s wage!

Author Harriet Martineau literally paid the price for her fame by being sent an unmanageable quantity of fan mail, hate mail, and prank mail.

In her autobiography, she writes:

“I dreaded the arrival of a thirteenpenny letter, in those days of dear postage.”

The amount due was calculated not only by the number of sheets of paper and enclosures but also by the number of miles traversed.

A letter enclosed in an envelope received double charge, so thoughtful people folded the letter and sealed it with a wax or sticky wafer.

Cross writing was common — a writer turned his or her letter horizontally and “crossed” (or wrote over) the original text at a right angle rather than use an additional sheet of paper.

If the recipient couldn’t pay, or made himself scarce, the letter was returned to sender.

The introduction of the penny-post in 1840 meant that for one penny a ½ ounce letter would be delivered anywhere in England.

In the words of the social historian GM Trevelyan, the penny post “enabled the poor, for the first time in the history of man, to communicate with the loved ones from whom they were separated”.

Especially, of course, at Christmas.

Mail delivered 12 times a day

In Victorian London, mail was delivered to homes 12 times a day. “Return of post” was a commonly used phrase for requesting an immediate response to be mailed at the next scheduled delivery.

It was possible (in London, at least) to mail an invitation in the morning, receive an answer in the afternoon post, and still have time to make preparations for dinner that evening.

John Keats finished “On first looking into Chapman’s Homer” at dawn one October morning in 1816, put a copy in the post at Southwark, and the recipient was able to enjoy the sonnet an hour or two later over his 10 o’clock breakfast in Clerkenwell.

People often complained if a letter didn’t arrive within a few hours.

Here’s one huffy letter to The Times complaining about the slowness of deliveries.

“I posted a letter in the Gray’s Inn post office on Saturday at half-past 1 o’clock, addressed to a person living close to Westminster Abbey, which was not delivered till 9 o’clock the same evening; and I posted another letter in the same post office, addressed to the same place, which was not delivered till past 4 o’clock in the afternoon. Now, Sir, why is this? If there is any good reason why letters should not be delivered in less than eight hours after their postage, let the state of the case be understood: but the belief that one can communicate with another person in two or three hours whereas in reality the time required is eight or nine, may be productive of the most disastrous consequences.”

Direct Mail

William Wordsworth, on the other hand, was disgruntled to receive all of his mail. He grumbled that all cheap postage had done was increase the number of time-wasting letters from strangers.

Postal Museum Blog describes how the Victorian mailboxes quickly filled with:

dress pattern books, advertisements selling leeches (for medicinal purposes), leaflets protesting the Corn Laws (expensive taxes designed to protect high priced British grain from more affordable foreign competition), life insurance solicitations, seed catalogues, and political mailings (e.g. protesting the evils of slavery or advocating peace and brotherhood).

Yep, junk mail.

Victorians began to advertise, send for, and receive by post tree cuttings, manure, medicines, seeds, venison, turtles, fish, and game, leading some Victorians to call the Post Office a “flying bazaar.”

In 1855 America, 30 or 40 mailbags filled with nothing but printed “circulars” for lotteries and patent medicines clogged up post offices every day.

The first Christmas Card

“In Victorian England, it was considered impolite not to answer mail,” says Ace Collins, author of Stories Behind the Great Traditions of Christmas.

In 1843, Henry Cole hit on an ingenious alternative to writing out hundreds of letters at christmas time. He asked his artist friend, J.C. Horsley, to design an illustration.

A London printer made a thousand copies of Horsley’s illustration—a family at dinner celebrating the holiday flanked by images of people helping the poor.

The image was printed on a piece of stiff cardboard 5 1/8 x 3 1/4 inches in size. At the top of each was the salutation, “TO:_____” allowing Cole to personalize his responses, which included the generic greeting “A Merry Christmas and A Happy New Year To You.”

The illustrated children holding up a toast in celebration caused a bit of bother with the temperance society!

Christmas Card Themes

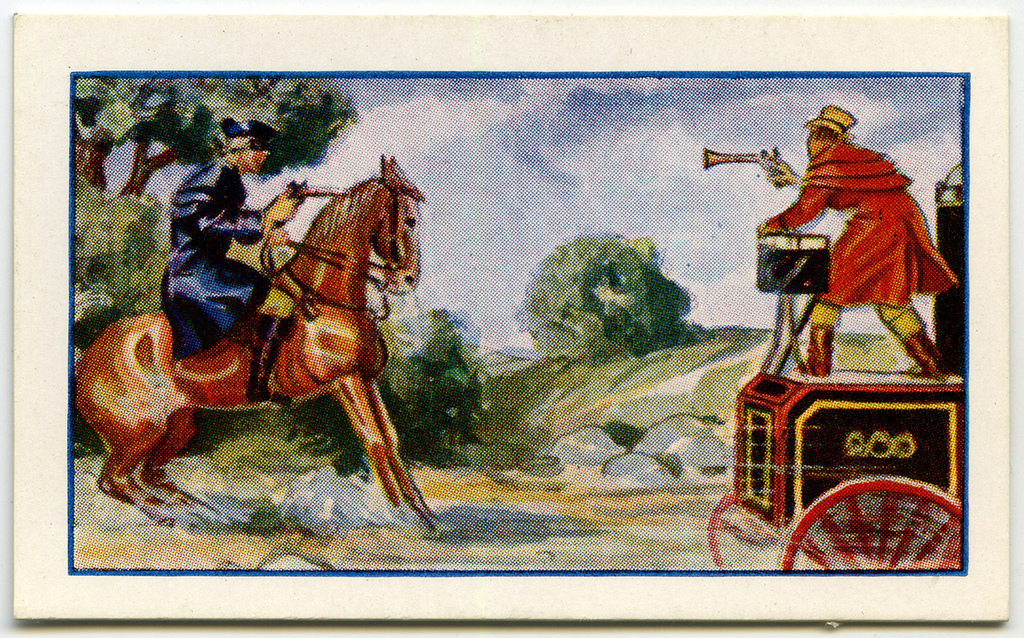

Commercial Christmas cards latched onto mail coaches in the snow as one of their favourite themes from the start.

The dashing mail guards swore loyalty oaths, wore scarlet tunics and had the right to shoot anyone they suspected of being an escaped French prisoner-of-war, with a £5 reward.

A contemporary complained in 1792:

“These guards shoot at dogs, hogs, sheep, and poultry, and even in towns to the great terror and danger of the inhabitants”

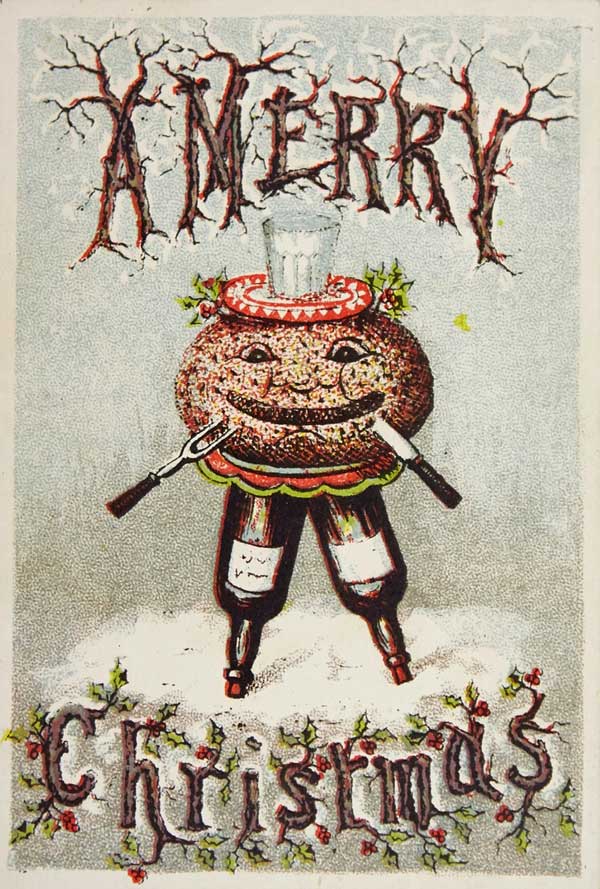

Other common Christmas card themes were dead birds, particularly robins, anthropomorphised Christmas puddings, and bugs.

Anthropomorphized Christmas pudding was a popular subject for Victorian holiday cards. Via the Laura Seddon collection at Manchester Metropolitan University.

“May yours be a Joyful Christmas”. The dead robin was a symbol of good luck during the late 19th century.

Makes one wonder what Mr Pooter received when he wrote in his diary:

“I am a poor man, but I would gladly give ten shillings to find out who sent me the insulting Christmas card I received this morning.”

By 1870, a newspaper was complaining about business mail being delayed due to the pile up of Christmas cards.

(The Daily Scrooge?)

Already by 1873, the entire Christmas card business all become too much.

People had started publishing ads in newspapers wishing their friends a happy Christmas and saying that they would NOT be sending cards that year.

If you enjoyed this, you may like the bizarre story of the Englishman who mailed himself.

You must be logged in to post a comment.